Intruder in my head: A story of hope

Contributed by Zeïneb Gharbi

One ordinary day

For four days straight, I’d been seeing double multiple times a day—watching TV, squinting at my computer screen, or just gazing out the living room window. It didn’t particularly hurt, but it did come with a side of the wobbles. I called around to a few optometry clinics to book an appointment. No dice.

So, I decided to head to the ER at Gatineau Hospital—but not before attending two back-to-back morning work meetings. Priorities, right? This was noon, November 5th, 2021. Back then, the intensive care closed at 6 p.m. on the dot!

I hopped in the car—blissfully unaware that I’d be spending the night at the hospital—armed with my headphones and a playlist of Anouar Brahem’s finest instrumentals. I had a faint suspicion that reading wouldn’t be an option during the impending waitathon.

Early that evening, a young ER doctor examined me. She seemed to have a hunch, but she stayed mum. Instead, she ordered a scan that revealed “something” in my head—and then informed me I’d be spending the night to get an MRI bright and early the next morning. She clocked out, and though I never saw her again, her gentle voice lingers in my memory to this day.

Still not particularly jolted—just mildly annoyed that I’d deprived my better half of our car that I had to leave in the hospital parking lot—I underwent the click-buzz-whir of the MRI and proceeded to wait for the neurosurgeon to interpret it. He had arrived that day from Hull Hospital, home of the neurosurgery team. (Nothing screams “don’t worry” like a neurosurgeon showing up.)

After spending a few hours listening to the famous Tunisian musician Anouar Brahem while meditating to distract myself from the sanitized white glow and bips, beeps, and muffled murmurs of the ER, I finally met him. He asked me the same questions from the day before, and then—as casually as one might discuss the weather—announced, “You have a tumour, ma’am.”

Unsure, I replied, “You mean, like a blood clot?”

Ah, denial—the mind’s secret weapon. “No, a tumour—a small meningioma, apparently lodged in the cavernous sinus.”

What ensued would be a whirlwind of consultations, explanations, scenarios, and a swift referral to the CHUM (the University of Montreal Health Centre)—all amid a backdrop of full pandemic and semi-lockdown (no companions and no visitors).

On January 5th, 2022, I finally underwent a craniotomy—an opening of the skull—to remove a small part of the meningioma—a non-malignant brain tumour yet one that nonetheless flips one’s life upside down. In all, the operation lasted eight hours.

I’m grateful for my luck: I have no motor, memory, or speech deficits. That said, there have been a clear “before” and “after.” Sensitivity to light and noise, excessive fatigue, low energy, and other little life annoyances have come with learning to “live with it,” along with continued MRIs and periodic neuro-ophthalmology exams. Today, my reality is living on borrowed time. But LIVE I will—fully, making the most of each passing day as it passes.

Where’s mental health in all this?

Anxious by nature, I’ve faced about every kind of mishap in my life—significant or not—with a knot in my stomach. This ordeal, however, was a new level. The first year of the COVID-19 pandemic was enough on its own, let alone brain surgery to boot.

Anxious by nature, I’ve faced about every kind of mishap in my life—significant or not—with a knot in my stomach. This ordeal, however, was a new level. The first year of the COVID-19 pandemic was enough on its own, let alone brain surgery to boot.

There’s no instruction manual for navigating such a (mis)adventure—especially when you’re signing up for the rest of your life. You can tap into your reserves, develop strategies and tools. For me, it’s above all been faith, accompanied by various meditation practices and their sidekicks: gratitude, self-compassion, and just plain acceptance. The support of loved ones around us—family, friends, and colleagues—is crucial, even when they think they’re doing very little for us. So often unbeknownst to them, they do more for us than they realize!

Fast forward three months later. I returned to work very gradually, fortunate to be part of a team that greatly facilitated my comeback. The key is to explain what support measures you need, go beyond the doctor’s terse note. In my case, management provided a flexible framework where I could start with modest goals until I bumped up to cruising speed.

This return to work wasn’t a straight line—not by a long shot. Regaining your intellectual capacities when you’re an analyst is no small feat. It’s also the attribute that largely defines us as professionals. My management’s flexibility allowed me to gradually recover all my abilities.

There’ve been shortened days, memory lapses, and moments of fluctuating alertness that persist to this day. My former hawk eyes don’t always catch every typo in what I write. I might stop mid-sentence to search for a word that just won’t bob up from the murky deep—not in French, not in English, and not in Arabic. Yet my team’s rooting always pulls me through as I rewrite.

A return to normal—really?

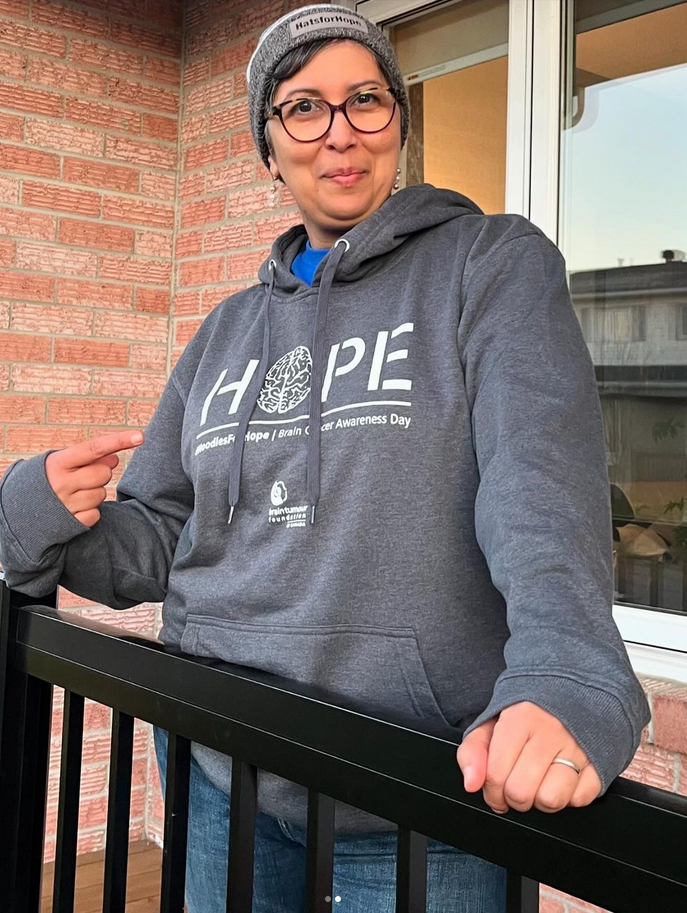

“The calm after the storm.” It’s no coincidence that Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada chose HOPE as the central theme for its activities. Funny how hope holds a unique meaning for each individual. For me, it’s a choice. Hoping is an intentional state of mind. Sometimes, you have to decide—every single morning—to “make it through” the day—the medical tests, the waiting for whatever comes next—as serenely as possible. It’s the constant, nagging reminder that anything is possible—even a complete remission.

“The calm after the storm.” It’s no coincidence that Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada chose HOPE as the central theme for its activities. Funny how hope holds a unique meaning for each individual. For me, it’s a choice. Hoping is an intentional state of mind. Sometimes, you have to decide—every single morning—to “make it through” the day—the medical tests, the waiting for whatever comes next—as serenely as possible. It’s the constant, nagging reminder that anything is possible—even a complete remission.

“Hope makes all the difference between hanging on and just letting go.”

It’s the quality of our presence and attention to life’s little details that makes all the difference. The aroma of that first cup of freshly brewed coffee slices through the haze of my early morning. The playlist I choose kicks up my motivational needle. The idea of another workday where I’ll learn something new or—better yet—help out a colleague or my boss; surprising the teens with a dinner they love at the end of the day; keeping one (or two or three) books within arm’s reach. All this often works better than a couple of Tylenol pills.

All this brings back a bit of reason to what seems to have none: why do I have to live with an intruder in my head for the rest of my life? Through small, daily gestures, the quality of our presence in our own lives that “the whole is greater than the sum of the parts,” as Quebec artist Ariane Moffatt so aptly put it in her song Miami.

My horizon is now only a matter of a few hours, sometimes three days, or when I’m lucky, a few months. Gone are the days of medium- and long-term planning. That’s part of letting go: “Keep calm, nothing is under control.” And it’s exactly then that life offers us its most precious gifts: new friendships, unexpected travels, enriching exchanges, and so on.

What was supposed to be the end

Anything can happen, but nothing lasts forever. Our ability to adapt to change, be resilient, and overcome challenges is a muscle that strengthens over time and practice. “One is not born resilient but becomes so,” to borrow the structure of a famous quotation that’s so dear to my heart from French existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir.

“There are good days and not-so-good days, when we need to dig a little deeper to find our hope, only to realize it’s always there, lurking in a corner of our soul.”

It goes without saying that I sought help. I underwent therapy and took antidepressants because a craniotomy is generally followed by depression (a little extra bonus!). I also relied on a support group and specialized webinars, and I dove into readings about brain tumours and related topics. These days, I read comics and graphic novels—and have no shame in that whatsoever.

A final word

Without losing an ounce of optimism, I went in for a follow-up MRI in early September 2023. A chat with my neurosurgeon a few weeks later revealed that the meningioma was slowly growing and putting more pressure on my optic nerve and pituitary gland.

Without losing an ounce of optimism, I went in for a follow-up MRI in early September 2023. A chat with my neurosurgeon a few weeks later revealed that the meningioma was slowly growing and putting more pressure on my optic nerve and pituitary gland.

I received a referral to the Gatineau Cancer Centre to explore the possibility of radiation therapy. The name of the centre set off alarm bells in my head (pun intended). I quickly realized that radiotherapy was my only option, so I embarked on 30 sessions—about fifteen minutes each—daily. The good news (after all, there’s always a silver lining) is that the facilities are just a 10-minute drive from home! A month later, the MRI confirmed that the treatment had worked: the meningioma had stopped growing.

Despite the side effects of all those rays beaming through my skull and brain, I navigated those weeks with a certain serenity—thanks to a fabulous care team. There was my oncologist, her pivot nurse, and the radiation technologists—always empathetic and smiling. Close weekly follow-ups allowed me to ask my questions and alleviate symptoms that piled up as I progressed through the treatment (nausea, head zaps, and extreme fatigue).

Today, all that is behind me. My new energy level is no doubt lower than before the treatment, but it’s entirely livable. I’m once again savouring life’s simple pleasures: walking outside, cooking, attending a theatrical play, and even joining a meditation retreat in a monastery for a weekend!

An endocrinologist is now guiding me to ensure my pituitary gland is functioning properly. I have periodic neuro-ophthalmology exams and MRIs. My gratitude goes out to all these health professionals who contribute to our survival. I continue to participate in Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada’s activities—the annual walk in June 2024, Brain Tumour Awareness Month in May, webinars with specialists and survivors, and much more.