It’s okay to not be okay – Laura’s story

It’s okay to not be okay.

During tough times, we often forget to remind ourselves of this simple truth. This goes double for caregivers, who often sacrifice their own wellbeing for the sake of their loved ones in hospital and their families at home.

For Laura Dill, it’s something she has come to embrace, but the road there was tough.

Within the span of two weeks in 2019, both her father, Gerry and mother Christine, were diagnosed with glioblastoma. Life, as she knew it, was irrevocably changed.

“There are no signs,” she says. “It’s mostly, ‘Fine, fine, fine… Oh my god you have a five-centimetre tumour and a year to live.”

That sudden diagnosis was entirely new to Laura. Her mother suffered a grand mal seizure on her birthday, while her father had some cognitive impairment for months prior to his diagnosis.

There is no way to deal with it except one day at a time, Laura says. The amount of unknowns and daily changes are impossible to keep up with, let alone anticipate.

Laura says she found support in a number of places, including Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada’s Ottawa support group. It’s been a helpful experience, she says, but notes that the caregiver experience is far different than that of a brain tumour patient.

Being a caregiver means splitting her days between two different hospitals. It means still being a mom, a wife, a friend and a sister, while also making time to visit both parents.

“I don’t know how I’m doing it,” she says. “I just do.”

Part of managing the reality shift caused by brain tumours – glioblastoma in particular – is dealing with things head-on.

It’s not a time for big plans, or what-ifs, or counting on favourable statistics.

The role of caregiver is something that anyone who hasn’t experienced it will never truly understand. While people offer their best advice and support, being told to make time to care for herself for instance, doesn’t help when the needs of her parents and her family life are so acute. People mean well, but well-intended words are often used to avoid talking about the concept of dying.

It is ugly, and it is uncomfortable, Laura says, but talking about it frankly is the best way to handle it.

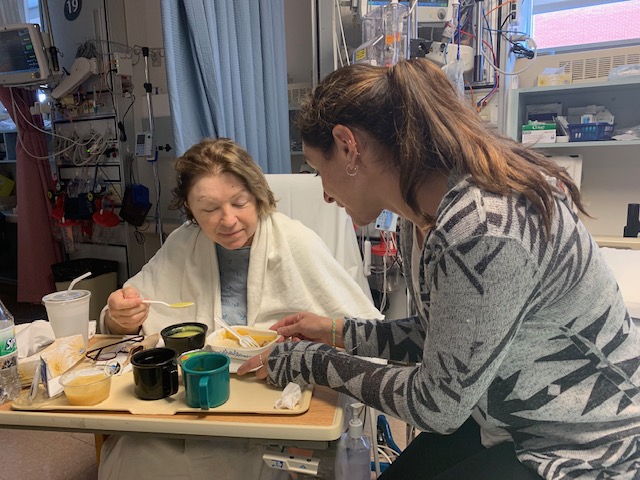

Laura is not afraid to share her experiences – good, bad or ugly. Photos of Laura with her parents in hospital show the grim side of brain tumours. Scars, hair loss, even bedside photos of her in full protective gear are all up for everyone to see on her social media feed.

It’s important to show these aspects, Laura says, though some feel she is doing a disservice to her parents in sharing images from hospital. However, people in the global brain tumour community have been resoundingly supportive. She’s received a shower of support from Poland, Spain, even as far off as New Zealand. People can relate, and reach out over continents to connect.

It reinforces Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada’s mantra – you are not alone. Sadness, suffering, transitioning from last moments to lost moments, are all a part of caring for loved ones with glioblastoma.

Laura has extensively documented all of these moments, with equal parts dignity, vulnerability, and humanity.

“It’s the part we don’t publicize and we don’t talk about,” she says. “I feel like it’s important to keep going and keep talking about it, helping other people to be more comfortable.”

Laura sees the way she is sharing her experiences as a responsibility. The topic of death and end of life weigh heavy on caregivers. Their suffering is real, even as they are doing their best to be strong for their loved ones. That doesn’t mean just putting on a brave face.

Crying, Laura says, is also strength.

“Because people are afraid to talk about this, I almost feel obligated – like it’s my duty to talk about this,” she says. “Just to say, ‘Hey, I’m suffering and this is hard.’”

One major realization caregivers make is they can’t be all things to all people. For Laura, that means being open and honest with her family when she needs time.

Helping kids understand a caregiver’s role is tough at the best of times, let alone being thrust into the situation on such an intimate level. Laura says being upfront is helping, but her kids still miss their grandma.

“They are seeing a lot more than most kids do at that age,” Laura says. “But I’m hoping it’s making them more empathetic.”

While their grandma can’t be present with the kids, they can still hear her voice in a teddy bear that has a recording of Christine. The kids made hug blankets decorated for their grandparents, with tracings of her kids, arms extended, to wrap them in a hug while they can’t be there.

Anticipatory grief is a big factor for caregivers and their families, which is only amplified by the mandatory distancing necessitated by COVID-19.

The pandemic has completely changed her role.

“Caregiving through this thing is non-existent,” she says.

In the week following March Break in Ontario, Laura was still visiting her parents in hospital every day. On the Thursday of that week though, it all ended. She and two other family members spent eight hour blocks with her father, who was only allowed one visitor at a time.

While her journey has been fraught with unexpected challenges, surgeries, drastic changes to her parents’ condition and a pandemic, Laura has been determined to use her experiences as a way to comfort fellow caregivers the world over.

It’s a tough calling and it’s rarely pretty. But for every person who connects – who has gone or is going through a similar experience with their own loved ones – knowing there are people like Laura out there offers reassurance that they are not alone in their struggle.

And that, more than anything else, can provide the strength to get through another day.